Motivation for code injections, for defenders and attackers

In a general sense, attackers use code injection techniques to mitigate defensive systems. This includes everything from bypassing host-based intrusion prevention systems, evading malware sandboxes and avoiding analysis by forensic tools. Naturally, malware has used these techniques for quite a while and even in back in 2013 Palo Alto reported that 13.5% of malware samples used code injections, described in the modern malware review report on page 16 under 'analysis avoidance '. In their report they also give an interesting insight about the motivation for code injections, namely 'Code injection was observed in 13.5 percent of samples. This technique is notable in particular because it allows malware to hide within another running process. This has the effect of the malware out of view if a user checks the task manager and can also foil some attempts at application white-listing on the host'. Wayne Low documents even before then, in 2012, the first analysis of the Gapz malware that explicility used a novel code injection technique that - due to it's novelty - bypassed host-based intrusion prevention systems here. Interestingly, the injection that Gapz deployed used techniques and ideas described around a decade earlier called shatter attacks, which was even presented at Blackhat in 2004 here.

In the years 2013-2019 the amount of code injections has continued to grow. There are currently many reports by anti-malware companies documenting the code injections in malware and I think it's fair to say that now, when a new malware is discovered, it's more often than not the case that it uses code injection techniques. A recent survey of techniques by SafeBreach documents 14 techniques invented in 2017-2019, and this leaves out 7 shatter-like attacks that they do not go in details with as well as a whole domain of techniques in the process hollowing space, in which several new variants have been discovered in recent years. Furthermore, malware samples are currently not limiting their injection lifecycle to only one injection technique, but a recent report shows that Dridex combines five different injection techniques.

Code injections are not only used by malware. Pentesters, and red teams in general, rely on these techniques to take control of the systems once they have gotten access to the system. For example, the famous Meterpreter used by pentesters rely on code injection as well as related techniques, e.g. self-loading DLLs. Shellterpro is another well-known pentester tool that is heavily based on code injections. As defensive systems get better, understanding the design space of code injections can significantly enhance the skills of red teamers, as it allows you to manually construct payloads and write injection tools that bypass the specific defensive perimeter of your target. An example of custom tools developed for the purposes of penetration testing was given at Blackhat in 2014 here.

Brief overviev of code injection foundations

In this section we give a brief introduction to some of the more common-known injection techniques.Traditional remote thread creation

This is the most well known injection technique and simply achieves execution in the target process by instantiating a remote thread. The general procedure is to get access to the target process using OpenProcess, allocating memory in the process using VirtualAlloc, writing malicious code to the allocated memory with WriteProcessMemory and finally having this code execute using CreateRemoteThread. Naturally, there are many variations of this injection technique, both in terms of getting access to the remote process, writing memory to the targets address space and also initiating execution. For example, instead of opening an existing process, the malware can create a new process with CreateProcess and inject its code in this new process or rely on lower-level APIs like NtOpenProcess. The attack can also write to memory using NtWriteVirtualMemory and creating the remote thread can be performed with a variety of lower-level APIs like RtlCreateUserThread, NtCreateThreadEx and ZwCreateThreadEx. This technique is perhaps the most commonly used by malware and example reports include Tinba and Emotet.

In general, we can construct a similar-looking attack in many ways. The primitive for writing memory to the target process need not be WriteProcessMemory, but can be any way of memory sharing. This includes memory mapped files by way of APIs like ZwCreateSection and ZwMapViewOfSection and also globally shared memory. Furthermore, from a programmatic perpective we can also use asynchronous procedure calls rather than explicitly starting a new thread in the remote process, which we discuss below.

Remote thread hijacking

A technique that is closely aligned with creating a remote thread is to hijack a remote thread instead of creating a new one in the target process. From a high-level point of view, the difference between this technique and the previous one is that the previous technique creates a new thread in the target whereas this technique hijacks execution of an exisiting one. One way to do this is to create a new process, by way of CreateProcess, in suspended mode and overwrite the entry point of the newly-started process such that it points to our attacker-controlled code instead. This effectively means the CreateRemoteThread call from before gets substituted with ResumeThread. A more aggressive approach is to simply suspend thread execution in the target process and then substitute the thread using SuspendThread. Code execution is then achieved by exchanging the thread context using GetThreadContext and SetThreadContext such that the registers of the thread context points to attacker-controlled memory. Naturally, since the thread execution of the target process is suspended it is in many scenarios desirable to restore faithful execution in the target process in order for the system to continue execution unnoticed.

The attacker can also initiate execution of the attacker-controlled memory in the remote process through asynchronous procedure calls such as QueueUserAPC, NtQueueApcThread, ZwQueueApcThread and RtlQueueApcWow64Thread. However, one of the drawbacks of doing this, however, is that the remote thread must be in an alertable state to trigger the APC.

Reflective DLL injection

In the previous methods we were mainly concerned with how to achieve code execution in the remote process. However, a question that comes up once you achieve code execution is what code to execute. In most cases just executing shellcode doesn't do the job as the attacker desires to have more comprehensive control. Reflective DLL injection is a technique that focuses on this aspect of the code-injection design space using a self-loadable DLL file. Specifically, reflective DLL injection is a technique that creates a DLL such that the DLL has a minimal Windows loader as an exported function. When this function is triggered the DLL will load itself inside the process of which it has been written, thus avoiding the need to be loaded from disk by the regular Windows loader. As such, it is not necessary to, for example, rely on calls like LoadLibrary to load a fully-fledged library inside the target process. Rather, the attacker can simply allocate space in the remote process, write the raw DLL content there, and then execute the exported function in the DLL itself. Lazarus is an example of malware that uses reflective DLL injection and pentesters published at Blackhat a white paper on a novel packer that uses reflective DLL injection here.

Process hollowing

A technique closely related to hijacking a remote thread is to simply substitute the entire memory of the remote process with attacker-controlled memory. Process hollowing does this. The steps in process hollowing is to create a process in suspended mode, then deallocate the memory of the suspended process (this is where the 'hollow' comes from), write an attacker-controlled image to the target process and then resume execution of the target process. Effectively, the goal is to explicitly hide execution of the malicious code in disguise of a benign process. Process hollowing is a commong techniques in malware samples, with an example report found here.

Example of advanced techniques

The majority of injections observed in the wild are of the types described in the previous section. However, (mostly) in recent years several novel techniques have been discovered that rely on approaches outside the scope of the previous techniques. These novel techniques use different API calls to achieve their code injection, sometimes rely on exploit-like techniques such as return oriented programming and are quite often specific to certain target applications. However, on an abstract level they still remain close to our most basic techniques as they still have to (1) communicate with the target process; (2) ensure attacker-controlled memory is written to the process and (3) trigger execution of attacker-controlled code in the process. It is important to emphasize in this blog post we only highlight some examples of these techniques rather than an exhaustive list. In particular, we have prioritised selection of techniques that have been documented to be used in attacks.

Ghostwriting

The main idea of GhostWriting is to force the target process to write malicious content in it's address space and force this code to be executed without calling any of OpenProcess, VirtualAlloc or CreateRemoteThread, or similar. GhostWriting achieves this by selecting two atomic gadgets (ROP gadgets), one that writes the value of a register to an address given by the value of a different register (mov [reg1], reg2) and another gadget that simply represents an eternal loop jmp 0x0. The technique then makes use of SuspendThread, GetThreadContext, SetThreadContext and ResumeThread to continuously overwrite memory in the target process. Specifically, it continuously sets the registers such that they overwrite a given address with the desired content, and then jumps to the eternal loop. As SetThreadContext allows the attacker to control the registers it is easy to overwrite the stack - or any other address in the target process - with whichever content the attacker desires. After the mov [reg1], reg2 gadget executes it returns to the eternal loop gadget, and the attacker gains control over the execution simply by calling SuspendThread, such that the execution does not run in the eternal loop forever. Rather, the 'eternal loop' is used as a temporary safe-state for the attacker to ensure consistency in the target process. A concrete example of using this is to to create a stackframe to NtProtectVirtualMemory that sets the necessary permissions for attacker-written shellcode. However, the technique used for achieving write-what-where and execute-on-demand is far more general and can be used to write any type of code to the target, e.g. a fully functioning PE file.

A quite interesting aspect of GhostWriting is that the technique was first made public in 2007, yet it still remains largely one or the more sophisticated techniques. The original blog post explaining the technique is available here.

PowerLoader and PowerLoaderEx

The idea behind PowerLoad is to abuse shared sections in Windows and overwrite several function pointers inside explorer.exe to point to attacker-controlled memory in the shared section. Since this shared section is non executable PowerLoader relies on a ROP chain to execute shellcode within explorer.exe. In more detail, PowerLoader first gets a handle to a window in explorer.exe. This window contains a pointer to a CTray class object, which is used for handling messages sent to the particular window. PowerLoader then uses SetWindowLongPtr to replace this CTray object, such that it now points to memory in a shared section. Within this shared section, PowerLoader writes its malicious code, which is a combination of a ROP chain as well as shellcode. PowerLoader then triggers the execution of the ROP chain by sending the window a message, using SendNotifyMessage. The ROP chain then overwrites a function within ntdll called atan with shellcode and transfers execution to this shellcode. This technique was first used by the Gapz malware and has since been generalised by researchers from Ensilo, that made the attack non-specific to the shared sections. You can find the source code for PowerLoaderEx here

AtomBombing

AtomBombing is another technique that uses ROP chains to get code execution in the remote process. Specifically, AtomBombing abuses the global atom table in Windows to share memory between processes and undocumented asynchronous procedure calls to force the target process into calling various functions on behalf of the injecting process. The injecting process writes a ROP chain and shellcode to the global atom table using the Windows function GlobalAddAtom. The injector then uses NtQueueApcThread to force the injected process to call GlobalGetAtomName to store the ROP chain and shellcode inside the target process. To invoke execution, the injector again uses NtQueueApcThread to force the injected process to call SetThreadContext to set eip and esp. Eip is set to the address of ZwAllocateVirtualMemory and esp is set to point to the beginning of the ROP chain. The injection is, therefore, achieved with a combination of NtQueueApcThread and GlobalAddAtom. An interesting aspect of AtomBombing is that not long after the publication of the technique an updated version of the infamous Dridex malware was discovered, that had adopted a modified version of the AtomBombing technique, and this is still being used in 2019.

Process Doppelganging

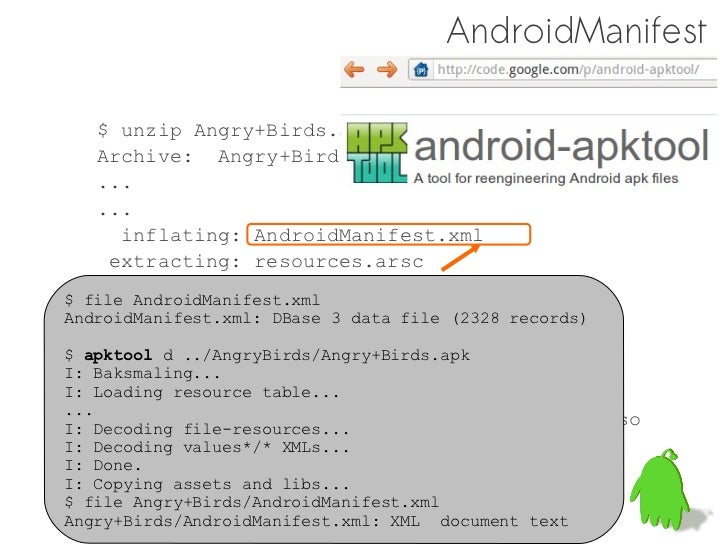

Smali

The idea behind doppelganging is to improve the limitations of process hollowing, namely how the executable memory is written into the target process. Doppelganging achieves this by way of Windows Transactions. Doppelganging loads a benign executable using CreateTransaction and CreateFileTransacted, but then overwrites the content of the transacted file with malicious code, using WriteFile. Doppelganging then creates a section that holds the tainted transaction, i.e. the transaction that holds the malicious memory, and then performs a rollback on the transaction. The rollback will undo the changes performed by the transaction, which in Doppelganging's context is the overwriting of the benign file, so the changes to the benign file won't actually be commited to the file system. However, the caveat here is that the content of the section still contains the tainted code. Now, doppelganging proceeds to create the target process with the content of the malicious section. Doppelganging creates the process in a low-level way using NtCreateProcess, and, therefore, has to perform various set-ups for the process to accurately execute, such as setting up process parameters and create the process's main threads. An example of Process Doppelganging in the wild was discovered in early 2018.

Earlybird

Early bird refers to a technique that performs a somewhat traditional code injection via remote thread instantiation early in the process initialisation phase. Specifically, the attacker creates a new process in suspended mode and then proceeds to allocate and write memory to the process. In order to trigger execution the malware uses an asynchronous procedure call and enforces execution of the APC call using the NtTestAlert function. The technique was discussed by researcher from Cyberbit and even though it received its own name, it is closely related to earlier techniques traditional injection. This is also confirmed by the fact that the injection dates back to at least 2012.

Smali Example

ctrl-inject

The ctrl-c key combination is a well-known pattern for exiting and shutting down applications. The ctrl-inject injection technique exploits the underlying features that makes this hotkey possible. Specifically, when a user presses the ctrl + c keyword in a console application a system process (csrss.exe) invokes a function called CtrlRoutine in a new thread of the given console application. The CtrlRoutine fetches the given handler for the control signal (ctrl + c) which contains a function pointer that will be called, which effectively is used to handle the signal. In short, the technique overwrites this signal handler with a malicious function pointer, such that whenever the signal occurs the malicious handler will be called.

The strengths of ctrl-inject is that the technique does not rely on any function calls like CreateRemoteThread, ResumeThread or SetThreadContext, but rather triggers execution through the csrss.exe process. The technique that triggers the execution is a simple ctrl-c signal which in many scenarios is considered harmless and unsuspicious. The drawback of the technique is that it only works with console based applications.

PROPagate

This technique was discovered in late 2017 and uses functionality of window subclassing to gain code execution in remote processes. Windows subclassing enables programmers to reuse functionality in existing controls by adding functionality and features to them. Whenever a window is subclassed, the messages to the original window is intercepted by the subclassing window which executes its own handlers before sending them on to the parent. You can read more about subclassing here. Whenever a window is subclassed it gets a new property called either CC32SubclassInfo and stores the data structures related to these properties in its address space. This property points to a data structure inside the subclassed process which contains a function pointer that gets executed in the event of a message being sent to the window. The idea behind PROPagate is then to write a malicious data structure inside the remote process and use the SetProp function call to point to this handler. The attacker then uses SendNotifyMessage to trigger the malicious function handler. Roughly 8 months after the first documentation of PROPagate by Adam, FireEye discovered the RIG Exploit Kit delivering a dropper that used PROPagate.

Shatter-style attacks

The final category of code injections that we cover in this course is called Shatter attacks. The basic idea behind these injections is to misuse the message-oriented way that windows are architectured within Windows. Specifically, whenever applications use windows they control these in a message-oriented ways which is a very modular and effective way of managing windows. For example, when a key is pressed a messaged is sent to the currently active window stating this key was pressed. However, the way these messages are handled by the active window is through message handlers, i.e. data structures, and at certain times these can be overwritten with attacker controlled memory. Since a window can send messages to other windows on the desktop and we can overwrite memory using previously mentioned primitives, we can start to construct code injections by overwriting the message handlers in our target processes and then sending messages that trigger the respective handlers.

Shatter attackers were first presented by Chris Paget (Now Kristine Paget) in 2002, however, the technique remains relevant. Recently, Hexacorn and Odzhan presented seven new ways of doing this.

Future outlooks

Code injections are continuously being used and there is a trend of increasingly more novel techniques being researched by defenders as well. For example, even in 2019 alone modexp has presented at least 15 novel injections (many inspired by Hexacorn), and modern malware samples use long chains of code injections to execute on the target system, such as the recent Dridex that uses five in total. The novel techniques are much more specific than the traditional injection attacks, and are now targeted internal structurse within the target processes rather than relying purely on common APIs. We can safely expect more exploit-like scenarios in the future and also new ways of enforcing process separation. Furthermore, even Academia is now in the field as well, both researching how we can use system-wide execution to construct highly sophisticated malware that operates across many processes (malwash) and how to generically analyse novel injection techniques. Code injections are here to stay and the complexity of them will increase. We highly recommend getting started with these techniques if you aren't already, and also predict that we will find more defensive tools and techniques being developed in the near future.

Conclusions

Code injections, also known as process injections, is an important topic in terms of post-exploitation strategies. Attackers, including both malware and pentesters, use these injections to execute code in otherwise benign processes as a way to bypass white-lists deployed by the defense products, e.g. host-based intrusion prevention and endpoint protection systems. From a defenders point of view we need to ensure our defense systems are aware of these tricks - and derivates hereof - in order to ensure our automated procedures are sound. Furthermore, from an attackers point of view, e.g. a pentester, these techniques can be of great benefit in order to secure access to a target machine. In this blog post we gave a motivation for both defenders and attackers on why studying code injections is relevant, and also highlighted technical aspects of several code injection techniques and attacks that use them.

This is a paid sponsorship by AstraZeneca. The content was developed by ONS and Margaret Barton-Burke, RN, FAAN, independently of AstraZeneca.

Large-volume (≥ 3 ml) intramuscular (IM) injections may not be administered often, and oncology nurses can be unfamiliar with best practices. A study found that only 32% of gluteal injections were administered into the desired IM target. This could lead to the drug being administered subcutaneously or near major nerves and blood vessels, potentially decreasing the treatment’s efficacy.

Faslodex® (fulvestrant), a selective estrogen receptor degrader indicated for advanced breast cancer as monotherapy or in combination with palbociclib, requires large-volume IM injections administered on days 1, 15, and 29 of each treatment cycle, then once monthly at 500 mg per dose. Fulvestrant packages contain two prefilled syringes of 250 mg/5 ml and 21-gauge, 1.5-inch general purpose SafetyGlide™ hypodermic needles. Each IM injection must be administered slowly (over one to two minutes) at two separate gluteal injection sites.

The proper method of administration of fulvestrant for IM use is described in the fulvestrant prescribing information:

Smali Files

- Remove glass syringe barrel from tray and check that it is not damaged.

- Remove perforated patient record label from syringe.

- Inspect drug product in glass syringe for any visible particulate matter or discoloration prior to use, and discard if particulate matter or discoloration is present.

- Peel open the safety needle outer packaging.

- Hold the syringe upright on the ribbed part. With the other hand, take hold of the cap and carefully tilt cap back and forth (DO NOT TWIST CAP) until the cap disconnects for removal.

- Pull the cap off in a straight, upward direction. DO NOT TOUCH THE STERILE SYRINGE TIP (Luer-Lok).

- Attach the safety needle to the syringe tip (Luer-Lok). Twist needle until firmly seated. Confirm that the needle is locked to the Luer connector before moving or tilting the syringe out of the vertical plane to avoid spillage of syringe contents.

- Pull shield straight off needle to avoid damaging needle point.

- Remove needle sheath.

- Expel excess gas from the syringe (a small gas bubble may remain).

- Administer intramuscularly slowly (1-2 minutes/injection) into the buttock (gluteal area). For user convenience, the needle “bevel up” position is orientated to the lever arm.

- After injection, immediately activate the lever arm to deploy the needle shielding by applying a single-finger stroke to the activation-assisted lever arm to push the lever arm completely forward. Listen for a click. Confirm that the needle shielding has completely covered the needle. Always activate away from self and others.

- Discard the empty single-use syringe into an approved sharps collector in accordance with applicable regulations and institutional policy.

- Repeat steps one through 13 for the second syringe.

- Traditionally, nurses have been trained to inject large volumes into the dorsogluteal site; however, the ventrogluteal site is evolving as a safer IM injection site (see TABLE 1 for an overview of both methods).

Nurses may also consider the Z-track method. See FIGURE 1 for more information.

- Consider the Z-track technique to reduce pain and prevent dispersion of medication into subcutaneous tissue.

- The Z-track method has been used to administer large-volume IM injections to reduce pain and subcutaneous tissue dispersion.

- Using the Z-track technique for IM injections prevents leakage of the medication into subcutaneous tissues and decreases the likelihood of localized irritation.

- Pull or push the skin 2–3 cm away from the injection site with the nondominant hand.

- Pierce the skin at 90° and depress the plunger slowly. If resistance occurs, pause then resume depressing the plunger.

- Withdraw the needle, then release the skin.

Fulvestrant is associated with injection-site pain, including sciatica, neuralgia, neuropathic pain, and peripheral neuropathy. Steps to minimize injection-site reactions include the following.

- Identifying bony anatomical landmarks and ensuring proper patient positioning offers a safe and effective means of IM delivery.

- Rotation of injection sites should be considered with repeated monthly injections.

- Use manual pressure before needle insertion to stimulate nerve endings and reduce sensory input during injection.

- Fulvestrant is highly viscous and passively warming to room temperature for 30 minutes before use has been suggested in the nursing literature. Alternatively, slowly rolling fulvestrant between the hands can minimize viscosity.

- Administer injections at a slow rate (over one to two minutes per injection).

- In patients with excessive subcutaneous fat, a 90° angle should be used to avoid injecting subcutaneously (see FIGURE 2).

- Be observant for factors that may increase the risk of bruising or bleeding (e.g., thrombocytopenia or anticoagulant use).

- Other steps to minimize injection-site reactions include the use of warm compresses and topical anesthetics.

Ongoing education regarding side effect recognition and management is important to help maintain patient quality of life and educate patients on queries such as how the drug will be injected, how often it will be administered, whether it will hurt, how they will feel the next day, and whether they will have injection-site pain.

An Interview With Margaret Barton-Burke, PhD, RN, FAAN

Q: A study cited in the poster noted that only 32% of intended gluteal injections were administered into the desired IM target. Do you find that this is a concern in the nursing community?

A: I would say absolutely, but specifically, this study reported gender findings and IM injections in women were found to be given more often into subcutaneous tissue. Women being given fulvestrant may not be getting their complete dose if the IM technique is not correct.

From a nursing perspective, it really begs the question, “How many patients are really getting fulvestrant administered in the muscle or subcutaneous tissue?” Nurses do not give IM injections frequently. However, for those that are required, are we giving these injections using proper technique?

Q: Do you often find that oncology nurses are unfamiliar with injection best practices?

A: I would tend to say no. Nurses are used to giving injections of all sorts and in a variety of ways. However, if a staff nurse is new to oncology, he or she may need to have a refresher on how to give an IM injection. Gail M. Wilkes, RN, MS, AOCN®, an independent oncology nurse consultant in Kilauea, HI, and I write a book every year called The Oncology Nursing Drug Handbook, and in that handbook, under fulvestrant, we recommend a Z-track technique. That is something you might learn in school but you might not use frequently because it is not a common way of giving an IM injection. In oncology, there is not much concern with unfamiliarity with injections, but more so with the type of injection

Q: Are there any other best practices that you recommend for these kinds of injections?

A: Best practices in the poster and manufacturer guidelines suggest splitting the dosage into two injections and administering into the gluteal muscle This is good practice both from a nursing and a patient perspective.

Q: What are the challenges nurses face when managing a patient who requires an IM injection therapy?

A: In general, the challenges are to be comfortable with giving an IM injection and to make sure that where you are placing the injection is into the gluteal muscle, avoiding the sciatic nerve. It is also important to consider our patient population, who tend to be at risk for bleeding. Being aware of the platelets counts and/or other laboratory findings are important prior to giving an IM injection. It is also important to be aware that these injections have the potential to be administered directly into a vein, and that is the main reason you check for placement by pulling back on the syringe when giving an IM injection. This should be done for all injections.

Q: What advice would you give to nurses to keep on top of education and updates surrounding injection best practices?

A: I am going to put on my ONS past president’s hat for a moment. ONS has a position statement that speaks to ongoing learning. After school or orientation, nurses do not stop learning, and that is the whole notion behind certification and keeping up your education.

Now I will put on my Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center hat. We have mandatory trainings yearly, and this is probably true for every hospital. Annually, I must complete trainings, and I had many trainings to complete initially when I came to the institution.

If a nurse has not given an IM injection in a while, he or she needs to say, “I have not given an IM injection for a while.” It is a clinical humility to admit when someone requires assistance. I would want, probably need, someone to walk me through the procedure. It does not matter how much education you have; my education has gone beyond the clinical area, and I think it is important to be safe in your practice. I would also read the drug information prior to administration.

I think nurses have an opportunity to conduct research and partner with other departments in the institution to replicate the Chan et al. study. We could corroborate or refute the findings from the Chan et al. study to gain the evidence for practice. We are all trying to use evidence-based practice.

Q: Can you give an overview of the pros and cons of using an IM injection therapy?

A: For the pros, you can give deep muscle injections with a larger volume and the drug is absorbed over time in an area that is rich with blood flow.

For the cons, depending on the size of the individual and where on the body the injection is given (i.e., into which muscle), we need to avoid the sciatic nerve and the large blood vessels. Also, in a cancer patient population, we tend not to give IM injections since our patients may have low platelets and a potential for bleeding.

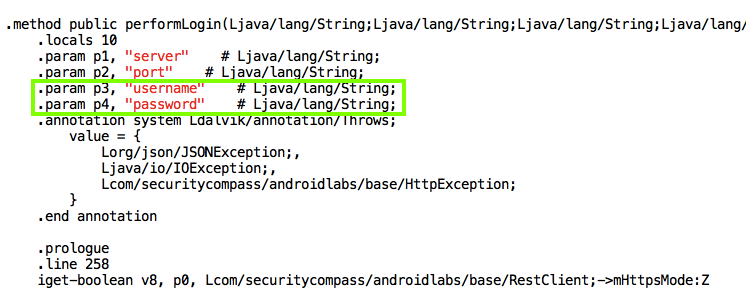

Smali Syntax

Another concern about IM injections is the pain. It is not comfortable if you give a large amount of solution, 2.5 ccs or mls, into each gluteal muscle. Nurses may have to pay more attention to rubbing the muscle a little bit more than you normally would after you give the injection due to the injected volume.

Smali Comment

The Chan et al. article noted that patients with a higher body mass index, which also equates to more body fat, may require a different length needle than what you would normally use for an IM injection. This article helped me think about IM injections in a completely different way.

The poster is well done. And not only that, it really points to some of the issues that I do not think we take seriously in oncology. I applaud the authors on their work.

Heather Vanderploeg, RN, OCN, BSN, CBCN, from AstraZeneca, and co-authors presented this information during a poster session at the ONS 42nd Annual Congress in Denver, CO. The poster was titled “Review of Best Practices for Large-Volume Intramuscular Injection of Fulvestrant.”

To discuss the information in this article with other oncology nurses, visit the ONS Communities.

To report a content error, inaccuracy, or typo, email pubONSVoice@ons.org.